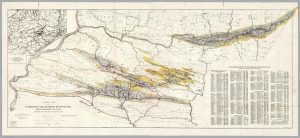

In the beginning of the summer, I thought I had the perfect envision for my research project. I had a solid research question, “How do Pennsylvania anthracite mining communities publicly represent their heritage?,” and a plethora of ideas to pursue. As the summer progressed, I realized that my scope was incredibly ambitious to complete in eight weeks. Instead of developing a two month research plan, I had created a much longer in-depth goal.

After some weeks, I had to find different ways to tighten my scope and realize a definite project by the end of July. As an undergraduate, having completed a successful research project is an invaluable experience. In two short months, I was able to expand on prior research that I partook in and expand my knowledge of a particular area of study. I really enjoyed finding a new niche and field — the intersection of landscape architecture and memory studies. Through extensive readings and applying certain theories, I have developed a new perspective to view the world and, particularly, my relationship with my hometown.

Additionally, I was able to learn more about the field of digital humanities and collaborate with my peers about how to integrate digital scholarship into our own classes. A great component about Digital Scholarship is that it encourages collaboration. It was an absolute pleasure to work in a student cohort with Justin, Minglu, and Rennie. Although we conducted independent research, throughout the summer we gave each other constructive feedback. Also, Courtney and Carrie were essential with keeping us on track and helping us work through the various digital platforms. It was great being introduced to many of the library and IT staff. I am so pleased to know so many wonderful people now.

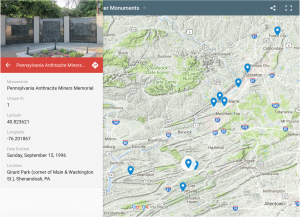

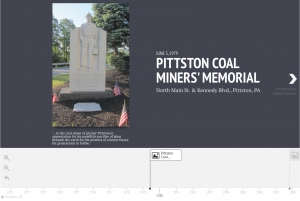

My final research project is a digital database curating ten monuments and analyzing their symbology and significance to the anthracite region. Also, by critiquing their urban spaces this illuminated how Shamokin has the potential to represent their coal mining heritage. The digital database is not an exhaustive list of monuments in the anthracite coal region of PA; however, it is a genesis of a much larger digital archive intended to establish a connection with a town’s history and heritage through public monuments.

My final research project is a digital database curating ten monuments and analyzing their symbology and significance to the anthracite region. Also, by critiquing their urban spaces this illuminated how Shamokin has the potential to represent their coal mining heritage. The digital database is not an exhaustive list of monuments in the anthracite coal region of PA; however, it is a genesis of a much larger digital archive intended to establish a connection with a town’s history and heritage through public monuments.

I created a “walking-tour” of the monuments by using a few different interactive platforms for the reader. There is a timeline, map, and digital gallery of the monuments. This allows the reader to view the monuments historically, geographically, and as a curation. There are newspapers for some monuments so that the reader can read about the importance of the monument through a public medium. There are also some photos analyzed for their symbology of the PA anthracite coal region, and I try to propose how Shamokin could represent their heritage as well. I encourage the reader to visit these monuments as well to experience their distinct urban spaces.

Please visit my site and feel free to contact me with any suggestions or information you may have!

-Tyler Candelora ’19 tdc008@bucknell.edu

Recent Comments